Thinking in 2023

How do people in the 2020s think?

“Uh… correctly?” might be the unspoken answer. It’s the assumption in every age.

A Medieval European might say the same thing… on her way to a witch burning. Enlightenment thinkers assumed their way of thinking would usher in a better, more peaceful world…before the most enlightened thrust us into the bloodiest century in human history.

Never considering how you evaluate truth is to let the spirit of the age pull you downstream without your agreement or even your recognition.

My goal in this post is to give you fins.

Now, my guess is that you have little interest in philosophy (alas, a trapping of our current age).

But as I look back on my own attempts to understand the world, the most important discovery was the most obvious: we are not the first people to try to make sense of life. So let me bring you into one of my favorite muses - the history of how humans in the west have thought.

“BORING. What’s in it for me?” you might rightly ask.

To be frank, without this basic history, it is impossible to understand the present state of western culture- the discussions and the arguments that will shape our future. Secondly, without an understanding of the different ways that people approach truth, the danger is that you yourself are co-opted into the bubble of someone else’s way of thinking without even knowing it.

That brings us back to our original question: how are we thinking in 2023?

The way I see it, we are in the middle of a winner-take-all cagematch between three very different epistemologies.

A New Word

Epistemology: a too-fancy philosophy term that simply means "how you know what you know".

So a toddler who knows what’s true about the world because mom said so has a "mommy epistemology". Your neighbor who reads his horoscope to know if he should start that business (or just curl up in the fetal position) could be said to have an "astrological epistemology".

Your epistemology is not a catalog of your beliefs - your epistemology is how you came to those beliefs. It is the rubric by which we know something is true or false.

This is a little meta, sure- but important. Despite the infinite expressions of human thought since the dawn of western civilization, in terms of how those beliefs arose, there have been three epistemological power players - and we are in the middle of their fight.

To understand them, go back with me for a second.

Mapping the Zeitgeist

The (Really) Old Days

Before farming, there wasn’t much time to think. We were too busy chasing berries, hunting buffalo, and otherwise reaping the curse of the ground. The “big thoughts” we did think were typically religious and spiritual in nature.

Farming brought food surplus. Food surplus gave us the time to do all the other things that we now know as “civilization” - including thinking like we had never thought before.

From one such civilization (Ancient Greece), there arose men who elevated logic and clear thinking to unprecedented heights. While most Greeks simply hoped the gods would be good and went on with their life, these “philosophers” asked big questions and tried to carefully reason their way to the answers.

Techniques and entire schools of thought cropped up around this systematic way of thinking, eventually trickling down (as philosophy does) from the philosophers to the culture.

For the first time, a rationalist epistemology was emerging,

Rationalism would survive the fall of Greece- but when its conquerors, the Romans fell, rationalism would (incredibly) go the way of the dodo for over a thousand years.

Before Rome fell, though, something incredible happened in the history of human thought. Constantine (the emperor of Rome) became a Christian - and Rationalism had a new rival.

The Age of Faith

Humans have always looked to spirituality and religion for answers to life’s big questions. But when Rome “Christianized” at the height of its power and (and then-height of western philosophy), religious thinking was levelled-up and infused into the culture with unprecedented thoroughness. Christian thought and Greek philosophy mingled, sparred, and more or less lived alongside each other. Until, somewhere along the way, the rationalism bestowed on us by the Greeks, was, essentially… lost. For over a millenia, we understood the world through the lens of church and bible (and sometimes superstition).

Origins, purpose, meaning - the church provided the answers. But more fundamentally, it provided a way of knowing.

Where did we come from? See what the bible says. How do I live a healthy, fulfilling life? See what the pope says. Where is the earth in relation to the universe? See what the church says.

To be a Medieval Christian wasn’t simply to believe the truths of religion- it was to know what was true by testing it against the stance of religious authority

For over a thousand years, the west had a religious epistemology.

Until the enlightenment turned that upside down forever.

The Age of Reason

If the Renaissance was Europe reacquiring its taste for Greek Rationalism, then the Enlightenment was the west getting drunk on the old 1000-year-vintage logic.

What was the enlightenmetn? Well, the characters are myriad and the effects incalculable (think everything from America to the iPhone). For our purposes, let’s simply zoom in on a short, French bachelor named Rene Descartes.

Perceiving a growing pressure from enlightenment thinkers, Descartes set out with a simple goal: to defend his beloved Catholic church against the assault of pure reason. His idea? To show that the truths of the Christian religion could be arrived at by reason alone - with no revelation required (Bible, pope, or otherwise).

In his Meditations he arrived at the same old biblical truths (the existence of God, the immortality of the soul, etc.), but in “showing his work”, he explicitly avoided using the bible as his standard of truth. Logic alone was enough.

Descartes wouldn’t understand the impact of his work until it was too late.

After being condemned by the church he was trying to save, copycats would soon follow - thinkers who loved how he thought (using reason alone) but who generally disagreed with his conclusions.

Modern philosophy was born.

The rational epistemology that had lain dormant since the days of Aristotle, was back - and this time on steroids. Science and Reason were in and the Bible was on the way out among the thinking class. But was Reason alone sufficient to guide us?

The Assault on Reason

For “rationalists” of the 19th century, the future couldn’t be brighter. Sure, there was a growing disparity between the different conclusions the philosophers were coming to, but with universally-accessible Reason and Science guiding the way (in contrast to faith-based claims), it was only a matter of time before Truth about everything from God to governance would emerge.

And yet…

Even in these halcyon days, cracks were already beginning to show. While Spinoza and Berkeley built their unassailable castles of rationality, Kierkegaard and Hume were loading enough dynamite into the cellar to blow the Rationalist project up forever.

Oh, Kierkegaard…

While Hume’s problem of induction called into question the truth value of scientific claims, across the North Sea, Soren Kierkegaard was getting fed up with Hegel’s rational co-opting of the Christian faith. He questioned the very value of cold, reasoned Truth altogether. After all, what good is a Truth “out there” that has no bearing on our day-to-day lives anyways? Isn’t our lived experience more important?

Beyond Truth

Rationalism’s heyday would continue into the 1900s (with the positivists pushing rationalism to the breaking point). But by the time the last Nazis were cleared out of Europe and the blood had dried on a second gruesome world war, the consensus among philosophers wasn’t just that God was dead, but the very project of modern philosophy (the sufficiency of Reason in search of Universal Truth) - lay as dead as the men on the beaches of Normandy.

My local library while I was in France, dedicated to Camus, a leading existentialist thinker)

Before any remaining rationalists could pick up the philosophical pieces after World War II, it was Jean-Paul Sarte and the French existentialists that would set the tone for philosophy in the latter half of the twentieth century. If God was dead, then meaning was for us to create. Perhaps there was no grand narrative to figure out. And even if there was, hadn’t the last century shown us the impossibility of one person reasoning to it from their limited, singular vantage point?

Maybe our own experiences of the world, finding and living our own “truth” was the best we could hope for. Maybe Nietzsche had it when he said “might makes right”. What if Truth wasn’t something out there to find through reason and argumentation, but just a tool, defined and then used by those in power to dominate.

Post-modernism, along with post-modern epistemology was born. And as it always has, this view of the world, this definition of truth, did not stay in the dusty halls of academia. What was once an odd, minority view held by disillusioned Europeans has found its way to the main stage- our culture.

Today

Do you still think this foray abstract or esoteric? If you take one thing from this post, let it be this: The thoughts that philosophers think become the thoughts that everyone thinks (about 100 years later).

Open a newspaper, scroll through your Twitter feed, or simply look around.

In our day the gender and even the race of a person is not determined by an objective measure, say XY chromosome pairs or genetic ancestry. That’s where a rational or even a religious epistemology would push us to. In our culture, gender and race aren’t up for argument. After all, if the postmoderns are right, there is no objective truth - so why can’t gender and race and anything else be determined by how an individual experiences his or her or zirself.

While Martin Luther King Jr. dreamed a dream in which his four children could “live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character”, critical race theorists dream of a day when color, gender, and sexuality are the primary means by which we are to be judged.

And of course, in just two decades, we’ve gone from outrage over Bill Clinton’s big lie to the acceptance- and celebration of- our first fully post-truth president, living and proclaiming his own truth on all things big and small - from weather to his own re-election. Facts be damned.

Ideas have consequences. And right now we’re living through them.

These developments in western culture are not random. They are the outworking of a 70-year-old view of truth that has finally made its way from the lecture hall to the town hall.

Signs of the Times

Still not sure about all of this? Look at how thought leaders of today are aligning themselves.

On the American political left, Bill Maher, long the prime mocker of all things conservative, has found common cause with the American right. After all, in the old days he could at least argue over facts. He is not alone.

Whether it’s Jordan Peterson becoming the Canadian posterboy for reason or Joe Rogan becoming the number one podcast on planet Earth, these “old” liberals (with their rationalist epistemology) have taken up common cause over something far more concerning than priests talking about the bible (religious epistemology). More fundamentally, with post-modern thought, we are staring down the barrel of the end of truth itself.

Similar schisms exist on the right, with some Republicans merely agreeing with our former president’s policies… and others ready to jettison little details like ballot counts and evidence. From a post-modern viewpoint, truth is secondary and narrative is king- the real game is power.

The Real Battle

This article isn’t to push you to a certain epistemology (much less a particular belief). It's to give us better categories and narratives than the ones CNN and Fox are using to profit from our fear and anger. The key battle of our time isn’t between left and right, black and white, or rich and poor. It’s more fundamental than that. The battle that will determine our future is over what truth is and how we arrive at it.

Will reason guide us? Is evidence and rational argument the way to discover truth - or will power grabs and propaganda be required to create truth? Long the source of our ideas about morality, equality and truth itself, what role will religious understanding play in the minds of westerners in this century?

For all the helpful critique that postmodernism has given us about the limits of reason and the importance of experience, we need think carefully about this view of truth - and the role that this way of thinking should play in our future.

The last great epistemological battle was between priest and professor - and it was intense. People died, power shifted, and we all view the world differently because of it.

You are living through the next great battle. Think carefully.

In 1832, Hokusai painted his famous “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji”. With each painting, he gave a fuller view of the mountain- and his own perspective. Here’s one of my “36 (or so) views of the world”. It’s an attempt to illuminate an aspect of the present by telling a story of the world through one lens. This essay covers one of my favorite (though admittedly abstract) lenses: epistemology.

Are the Big Questions Dead?

“Am I living it right?”

- John Mayer

"My purpose is whatever I make it”, "What does it matter if God is there?" "Haven't we moved beyond these old questions?"

As quickly as these sentiments have seeped into the modern psyche, it's worth noting that “the big questions” about meaning, God, and reality are still, well… big. There’s (still) a lot at stake.

It's not that everyone has always agreed on answers to huge topics like purpose and the existence of God. On these, men and women have come to all kinds of conclusions. But ever since Socrates reminded us that “the unexamined life is not worth living” thoughtful people have joined in common chorus around one big idea: the meaning of your life and nature of reality are worth figuring out.

And yet, most of us live without asking big questions. We go to church or mosque or skip religion altogether without asking “why?”. We believe what our parents asserted or we just drift with whatever our culture is pushing at the time.

It’s tempting to pass topics like meaning and God off as “esoteric”, but the reality is that these questions lie inches below the surface of our daily decisions, experiences, and longings.

Stumbling into Depth

Underneath “What should my major be?” or “Should I have kids?” lie whole root systems of assumptions which can only be probed with deeper questions.

“What is a job for?” “Why should I (or anyone) go through the risk and pain of having kids?”

Now we’re getting somewhere. Brave souls can dig one level deeper.

What is the purpose of my life?

Is there some objective meaning to my life? Or do I make it up myself?

But where would objective meaning come from? There is one candidate…

…Does God exist? What is he like? What might he want from my life?

For some of us, this just got real uncomfortable real fast. Like any good Minnesotan, I too sought to push aside “the big questions” - or at least keep them to myself.

Eventually, my Scandinavian heritage would yield to my inner engineer. In trying to be intentional with my life before I lived it, asking big questions became necessary.

I’m not trying to convince you of an answer. My contention is simply that big questions are not dead. They are worth asking.

Here are a few reasons why.

Ask Big Questions to Clarify Your Purpose

“Begin with the end in mind.” Stephen Covey's second immortal habit is as obvious as it is rare. Covey argues that no project, business, or relationship should be launched without first asking what end are we are trying to achieve, because the steps we take will follow from our purpose.

The same goes for life.

And yet, most of us spend more time planning our vacations than planning our lives. Maybe that’s because to plan our lives, we need to decide what life is - and this can be difficult and scary.

Our present culture tells us that "life is whatever we want it to be". This might be true. Or it might be a accidental byproduct of the "expressive individualism" that rules our tiny, privileged time and place.

To find out we have to ask.

2. Ask Big Questions So You Don’t Miss Out

I’ve noticed a funny theme in my bible reading lately. I’d call it “The Life within life”. It’s all over the book, but let’s just look at a couple passages that become weird when you stop to think about them.

Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of God.

-Jesus, Matthew 4

Isn't life more than food and clothing?

-Jesus, Matthew 6

Wait, what? We all know people who seem to get by just fine on “bread alone”, without a care for “every word that comes from the mouth of God”. We know people who are very much “alive” with mere “food and clothing” and a full 401k, etc. These are people whose primary concern is their physical needs now and in the future. That’s normal. It’s common. It might be you.

Jesus is saying that you can be alive while at the same time missing out on Life. He’s claiming there is a deeper dimension to what life can be.

Is he right? Or is he full of it?

To find out we have to ask.

3. Ask Big Questions to Understand your Foundations

We all believe in things like free will, morality, and human rights. We can't help it. But for these features of reality to make any sense, we need God.

We’ll all take moral stances in our lifetime, both big ("Putin has no right to invade Ukraine") and small ("She has no right to treat me like this"). We'll assume people matter. We'll act like decisions are real.

Are we standing on solid ground when we do this? Or are we just being illogical robots living in cognitive dissonance?

To find out we’ll have to ask.

4. Ask Big Questions While You Can

Voyager’s iconic picture of Saturn’s rings (750 million miles away)

I just read a fascinating story about the Voyager space mission. The project stemmed from a crucial discovery by Gary Flandro in 1964. Flandro found that Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune align once every 176 years, making a long-range mission possible. Also - the next alignment was in just thirteen years. NASA frantically built Voyager and launched it just in time. Any later and we’d have missed the window.

We want to believe that timing doesn't matter. That life will wait around for us and that we'll always have the opportunity.

The Voyager story teaches us that windows of discovery don’t last forever.

And that's exactly how the Bible talks about life.

The picture that emerges from the ancient book is that now is the time to figure out what life is about (e.g. here, here, here). There are consequences for the answers, both now and later. Is that right? Or a bunch of religious nonsense?

To find out we’ll have to ask.

Conclusion

Friend, I don't know where you're at on this journey. Maybe you've already reached conclusions on the big questions of God and meaning or maybe you're asking them right now. Perhaps you have asked the questions but you’ve drifted away from the answers you know to be true.

Or maybe you've lived your whole life climbing the ladder in front of you without asking if it was the right one.

Big questions can be scary. I can't say where you might end up. But you never know - until you ask.

The Making of Everything

"The first question that should rightly be asked is, "Why is there something rather than nothing?"

-Gottfried Leibniz

Before you read this essay, pause. Breathe. Look at your hand as it touches your computer or phone. Feel your arms and legs. Look around the room to see light as it hits your surroundings.

Your body, your thoughts, you are here on a giant ball we call earth, spinning out into an incomprehensibly large span of cold, heat, light, and matter that makes up the known universe.

Where did all this come from? Why is there anything at all?

You wouldn't be the first to ask. The question was first penned by the Greeks, but my suspicion is that it's been asked by thoughtful people since the dawn of human history.

Let's think about it.

Does the Universe get a Pass?

First, can we assume that everything (including the universe) has some sort of reason or cause for its existence? It seems far more likely than not. Everything in our experience has a cause. We exist and we have parents to thank. The trees in your yard are a result of seeds, water, sunshine and time. Science itself proceeds under the assumption that things are the way they are for a reason - and we can inquire what that reason is. Even those old sparring partners, Ken Ham and Bill Nye, can at least agree there are causes for the things we find in the world and we can know something about those causes.

Universe:

Is the universe itself exempt? Or would something that big, that all-encompassing cry out for a reason even more? The converse - that things exist without reason or cause and we shouldn’t ask why they exist - strikes me as a little absurd… and at least unlivable in the real world.

The universe must have a cause just like anything else - and Plato and Aristotle agree (phew).

This leads to a second question - what would cause a universe to come into being?

Making a Universe

Whatever made the universe is powerful beyond our wildest imagination. The hubble deep field tells us there are roughly 125 billion galaxies - and those are just the ones we can observe. What kind of power could make these?

Second, the cause would have to exist outside of space and time as neither space nor time (by definition) existed before the creation of the universe.

This seems to be consistent with modern physics, which tells us that it wasn't just matter that was created in the beginning but also space, time, and the laws of physics themselves.

In short, if the universe had a cause, the cause would be mind-bendingly powerful, eternal, uncaused, and immaterial (and possibly personal).

So what does all of this mean?

Let’s dust off our thinking muscles and turn those little paragraphs above into premises. Smash them together you’ve got yourself an argument (the cosmological argument to be exact - you philosopher, you).

The Argument

The summary would look something like this:

Everything that exists has a cause

If the universe has a cause, that cause would be powerful beyond imagination, eternal, uncaused, immaterial, (and possibly personal)

The universe exists

The necessary conclusion of this argument is that the cause of the universe is a powerful, eternal, uncaused, immaterial, (and possibly personal) entity. We haven’t “proved” the God of the bible by any means, but we’re getting warmer.

You might like that conclusion or you might not. The conclusion follows from the premises and from my seat, to deny the premises is to land in some weird places (philosophically and practically).

You might have questions - objections, even. To summarize a few objections in a borderline-offensively short way, I’ll just give some quick thoughts on these.

Why does God get a pass on being eternal and uncaused and not the universe?

If you were paying attention, premise 2 (the one about uncaused, eternal, etc.) wasn't put there because we need to exempt God but because that's the sort of cause a finite universe would require.

What about the multiverse?

A few issues with multiverse theory, not the least of which is that we’d now have to explain multiple universes.

What about Quantum Theory?

I love quantum theory, and I hope to dive in someday with the blog. For our purposes here, if you’re banking on quantum fluctuations to create everything from Andromeda to Dr. Seuss, my first question would be where the energy-dense quantum vacuum came from (along with the laws to govern it)?

Conclusion

For me, the cosmological argument has always been persuasive at a gut level. To say that there is no reason for the existence of the universe seems as unlikely as it is unsatisfying.

I wouldn’t call this a “proof”. I don't really believe in proofs, especially for God. To me, it’s just another pointer.

Over the years, thinkers have found ways to try and wiggle out of the conclusion (see Hume for old objections, Krauss for new ones). You'll have to judge if they've been able to do so.

For this armchair philosopher, if it's good enough for Aristotle (and Aquinas and Anselm and Descartes and Leibniz), then just maybe it's good enough for me. Or as Glen Scrivener put it recently:

“Christians believe in the virgin birth of Jesus. Materialists believe in the virgin birth of the cosmos. Choose your miracle.”

History’s Greatest Linchpin

And if Christ has not been raised, our preaching is useless and so is your faith.

-The Bible

The Only Question That Matters

If you want to disprove Christianity, don't go to the age of the earth, evolution, or weird stuff in the bible- go to the resurrection. It's Christianity's self-described linchpin.

But in 2022, how much can we know about something that happened two millenia ago? Turns out, a lot. The resurrection story isn't just unique in what it claims, but also in its early and prolific historic documentation of those claims. No one’s asking you to “just have faith." You’re going to need your brain for this one.

It turns out you don't need to believe the bible is an inspired book to believe in the resurrection. Feel free to treat the bible like any skeptical scholar would treat it - as a historical document with numerous claims of varying reliability.

So which biblical and extra-biblical claims are well-founded historically and relevant to the all-important "back from the dead” question? Here are the cliff-notes, an honorary degree in resurrection studies from Average Joe University. Turns out there are a few basic facts that scholars of various theological (and a-theological) viewpoints agree on.

The Facts

Here are some largely agreed upon facts from New Testament Studies:

1) That Jesus died by crucifixion;

2) That very soon afterwards, his followers had real experiences that they thought were actual appearances of the risen Jesus;

3) That their lives were transformed as a result, even to the point of being willing to die specifically for their faith in the resurrection message;

4) That these things were taught very early, soon after the crucifixion;

- Gary Habermas,“Minimal Facts on the Resurrection”

There’s nothing explicitly supernatural here. Some scholars might disagree with one or two, but they fight an uphill battle in opposing the established consensus view on each one.

The million dollar question, then, is what story best makes sense of these facts?

We don’t need blind faith - we need (our inner) Sherlock Holmes. We need to construct hypotheses, test and eliminate, and choose the best one. Over the years, many have done just that.

Sherlocking the Resurrection

We should prefer natural theories over supernatural ones. So over the centuries, naturalistic reconstructions (accounts without God or the supernatural) have been put forth to account for these facts. They fall into four buckets:

Legend creation: The story was changed / embellished over time.

Mass hallucination: Disciples only thought they saw Jesus back from the dead.

Jesus didn't really die: It just looked like he did. This is actually the Muslim take, FYI

Conspiracy Theory: Disciples stole Jesus’ body and lied about it.

To be “blogpost-level-concise”, these theories all suffer from fatal flaws.

Legend creation: There just wasn't enough time that passed for legends to develop.

Mass Hallucination: While hallucination is very much a thing, mass hallucination is not.

Not really dead: Roman soldiers were experts on human death. Also, crucified people left in a cold dark tomb don't recover without medical help. Here’s a dramatic youtube refutation of this view.

Conspiracy: Grief-stricken, disillusioned groups of fisherman and tax collectors don't come up with paradigm-shifting religious ideas, pull off the greatest conspiracy of all time, and then die for ideas they know are false.

An Inconvenient Truth

"When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth."

– Sherlock Holmes

Of course, there is a theory that makes perfect sense of these facts, but the theory comes loaded with implications for the universe… and our lives. And we don't always like that.

Most of us would rather suppress the truths that are too uncomfortable to handle, particularly those about God.

The theory that makes sense of the facts is that Jesus died and then came back from the dead.

If that is the case, his life and teaching deserve a closer look.

Conclusion

At the beginning of my search, I thought I needed to figure out if I believed in God first, and then peruse the entire canon of world religions, painstakingly working through Muhammad, Jesus, Buddha, the bible, the problem of evil and suffering, and all the rest.

For me, it ended up working backwards. In zooming in on the resurrection of Jesus, I came to believe that Jesus had really died and had really come back from the dead.

The implications of that one conclusion informed many of the other questions I had. The existence of God, the afterlife, and the truth status of other philosophies and religions all found their answer in who Jesus was - the resurrected Son of God.

The answer gave me some rope to keep believing when I came across difficult things in the Bible or the world that I didn’t like or understand. Most importantly, it made me want to listen to what the guy said.

Of course, this is just my take on the all-important question. We must all answer the question Jesus asked Peter all those years ago.

Who do you say that I am?

Comment

What are your thoughts on the resurrection?

Subscribe

Read More

Popular: Case for Christ (it’s also a movie now, apparently)

Academic (long): The Resurrection of the Son of God

A Shortcut for the Spiritual Search

“Anyone who really wants the truth ends up at Jesus”

-Johnny Cash

Jesus said he’s the way, the truth, and the life. For me, he was the shortcut too.

After my summer of doubt, I was consumed by a question: How do you go about figuring out which religion or philosophy is true when there are so many out there?

It had dawned on me that the menu of religious and philosophical options is less like Chipotle (“black or pinto?”) and more like a Chinese restaurant (“I'll take #17 and my wife will have… #46?”).

Faith options come in endless flavors - eastern and western, new and old, secular and theistic. When forming a worldview, where do you even begin?

Turns out, you should start with Jesus.

I know what you're thinking: "Ok, Mr. Biased Now-Christian. Of course you want us to start there."

Sure, I'm biased towards Christianity for reasons we’ll get to below. But I'm also biased toward efficiency - and if you can make your mind up on Jesus, you narrow your search considerably.

It's like an old game from millenial past…

Playing Guess Who with Jesus

"Does the person have glasses?"

"Yes"

[flips down all but 3 people]

I'm looking at you, in the second row, Joe…

Mathematicians know that in “Guess Who?” better questions lead to faster answers. For spiritual seekers, “deconstructers”, and doubters, the same principle holds true.

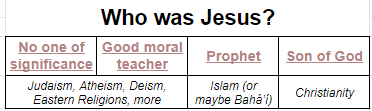

In “Worldview Guess Who”, “Who is Jesus?” is the most strategic question you can ask. Why is that?

Jesus the founder of the world’s most popular religion - in looking into him, you’re starting with the most worshiped person in human history.

His claims are unique among major religious figures. Buddha, Muhammad, and Moses never claimed to be God.

You’re killing multiple birds with one stone. Because of his incredible claims, other religions are forced to make a call on who he was, either explicitly (e.g. Islam) or implicitly (e.g. atheism, Judaism). In studying Jesus, you’re actually sifting through multiple major religions at the same time.

Making up your mind on who Jesus is (either way) will clear out a huge chunk of the board.

If Jesus is no one of significance, didn't exist, or is just a good moral teacher, you can cross out the worlds' two most popular religions in one go (Islam and Christianity). If he's just a prophet, get out the burka because you, my friend, are now a Muslim. If, however, he is more than that - say, the Son of God, then we’ll need to take a closer look at his life and teachings.

“Ok” you’re saying. “Start with Jesus. But isn't the Jesus question intertwined with other contestable questions like biblical inspiration and if there is even a God to begin with?”

Not for our purposes. While existence and inspiration are big issues, let’s bypass all of that. If we can make a call on if the guy really died and came back from the dead, we’ll have the most important piece of data available. The implications to that answer will tell us a whole host of things about the existence of God and the truth status of the most popular religions in world history.

To summarize, for spiritual seekers:

Jesus is the shortcut

His resurrection is the shortcut to the shortcut.

But surely, I wouldn’t introduce such a big topic in the medium of a blogpost? Oh shoot- turns out I did.

Comment

Who do you say that he is?

Subscribe

We All Believe

Why do some people believe in God while others don't?

The Bible gives a weird answer that I didn’t understand for a long time.

If I were writing the Bible, here are verses I would include:

"Some people are just more inclined to religion than others"

“We're all just doing our best with the evidence in front of us"

But those verses aren’t in the bible.

Here's what is in the bible:

“For the wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men, who by their unrighteousness suppress the truth. For what can be known about God is plain to them, because God has shown it to them. For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse.”

-Romans 1:18-20 (my emphasis added)

That is a controversial description of belief in God.

The writer is saying that:

Every human believes in God (v.20)

His existence is plain to anyone who's living in the world (v.19)

Rather than embracing God, humans suppress the knowledge of God (v. 18)

For years, I thought this was silly. Was Paul really saying that Richard Dawkins (or [insert your favorite atheist here]) is really some sort of closet evangelical?

Kind of.

He's saying that God has baked his "invisible attributes" into "the things that have been made" (i.e. us and the world). We don't need to be scholars or philosophers to perceive him- the answers are right there in our everyday lives - in how we live.

Things like free will, good and evil, human rights, logic, beauty, meaning, love, the existence of matter itself. These things aren't the end of a syllogism. They are perceived by professor and plumber alike (v. 20). And those things don’t make sense without God.

We all live like God exists. But because of what acknowledging God might entail, we simply take these features of God’s world - and deny the God who made it. We embrace cognitive dissonance.

So secular conservatives point out government corruption, the importance of free "choice", and the inherent "evil" of totalitarian states. Secular liberals argue that Black Lives "Matter" and fight for abortion "rights" and denounce corporate greed. Even Richard Dawkins can't help going on moral crusades despite his moral-less universe.

Without God, all of this is inconsistent foolishness. It's denial.

Once I understood this Bible passage, I started seeing it all over.

A gay rights rally? Just an odd way of people saying they believe in God (from whom do rights come?).

Someone calling out Donald Trump for his latest scandal? Another profession of faith (from where does morality come?).

Black Lives Matter.

Women's right to choose.

#MeToo

Immigration.

Environment.

God, God, God, and more God.

"But this is just sloppy thinking on the part of non-theists" you might respond. "Surely, the more thoughtful among us can avoid this." Not so. We all live like God exists.

Here's what Romans 1 looks like in high-profile intellectuals who are clearly not fans of God - but live as though He is real as their mothers.

Bertrand Russell on Morality

I have no difficulty in practical moral judgments, which I find I make on a roughly hedonistic basis, but, when it comes to the philosophy of moral judgments, I am impelled in two opposite directions and remain perplexed.

-Bertrand Russell

Possibly the most famous atheist of the 20th century, Russell was famous for his vocal, wide-ranging moral stances on world government, women’s rights, marriage, and war. He also didn't understand how someone could believe in objective morality.

Galen Strawson on Free Will

"[The impossiblity of Free will] can be proved with complete certainty"

...

"I can't really live with this fact from day to day. Can you, really?""

- Freedom and Belief

Albert Camus on Meaning

“There is only one really serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide."

Despite Camus’ academic views on the meaningless of his (and everyone’s) life, he would work tirelessly towards multiple causes throughout his life including the French Resistance in WWII and a wide range of moral issues.

Christopher Hitchens on Human Rights

Christopher Hitchens was a well known atheist (of New Atheist Fame). While he would make a career out of arguing for God’s non-existence (his magnum-opus on the topic being “God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything”), he also would take a number of moral stances throughout his life - including, surprisingly, being against abortion.

We don’t always want to believe in God, we just have to live like he’s there.

Comment

Where do you see cognitive dissonance in the world today? Or in yourself?

Subscribe

Share

Who could benefit from this post?

The Inescapable God

It's hard to live like there's no God - it might be impossible.

Many in the west are dropping God from their worldview. They may or may not realize that they are picking up a new worldview (one without God).

Few that adopt a God-less worldview work out its implications. Fewer still live by those implications.

Most of us (actually all of us as we'll see) believe in things like free will, human rights, morality, justice, and meaning. These things make perfect sense within a Judeo-Christian worldview. Made in the image of God, we are given a purpose, dignity and worth, and a moral sense to comprehend the moral law that permeates the world.

If there is no God, none of those things are real. Free will, morality, human rights, and meaning in life are fictions.

What's wrong with believing that?

Nothing... except real life.

Free Will

There is no free will in a universe without God. We are just biology. Biology arises from chemistry, chemistry arises from physics, and physics tells us that we are simply a bundle of atoms.

Atoms don't choose. Their location and velocity depends on prior location and velocity. There's no "free will variable" in Newton's laws or quantum theory - it’s already determined. In a universe without God, it turns out that we are robots.

But try to live a day denying that you have free will.

Try it in the burrito line at Chipotle. Notice when convincing a friend to watch a TV show or come to a party. Consider when you criticize the president for what he did or didn't do.

You're assuming that you, your friend, and the president have a choice. If it was determined, why argue anything? It's already determined.

My personal favorite is when someone tries to convince someone else that free will is not real (cue Alanis Morissette).

Is this an accurate description of the world and our experience?

In the philosophy room, it's easy to dismiss God. But real life is stubborn. It grabs us by the collar and forces us to believe in things like free will. We can't function without it.

But for free will we need a worldview that includes God. When we make a choice, when we argue or protest someone's actions, we are believing that free will is real.

We live like God exists.

Morality

There is no morality in a universe without God. Matter is all that is... and it just is. Arguments over morality are like arguments over which color is the best - one person's feelings against another's.

But try living a day without morality.

Read about the latest murder. Remember armed jihadists taking over a plane of terrified travelers and crashing it into a skyscraper. Let the reality of millions of little boys and girls on the trains to Auschwitz (and those bringing them there) sink in.

Think too about the social workers, policeman, and teachers working to make our world a better place. Think about the firefighters climbing up World Trade Center stairs, saving lives and giving their own. Think about families across Europe risking their lives to harbor their Jewish neighbors.

Is the firefighters' bravery the same morally as the Jihadists' murder? Are Adolf Hitler and Josef Mengele the same morally as Mother Theresa?

They are in a universe without God.

In a world without God, might is what makes right. Without God, survival of the fittest is our ethic and there's a strong case to be made that the Nazis were performing a moral good.

Is this an accurate description of the world and our experience?

If God exists, there is a transcendent moral code that exists across space and time - and we know it. If God exists, we can condemn slavery or the Holocaust even though those in power believed it was right at the time. If God does not exist, we can't.

When we condemn war, child abuse or genocide, we are saying that morality is real.

We live like God exists.

Human Rights

There are no human rights without God. A person has the same instrinsic value as a puddle of mud. A child is as valuable as a lawn ornament.

But try living a day without believing in human rights.

"Black Lives Matter". "Blue Lives Matter". Without God, the only lawn sign that makes sense is one that says "No Lives Matter".

Gay rights, civil rights, women's rights - all fiction.

What are "rights" in a material universe? When did they come into existence? How do you know they are there? Why should we abide by them?

In a world without God, a society that wanted to get rid of a people group, could simply decide that it brings utility to the rest and get rid of them - without argument. It would be the right thing to do.

Is this an accurate description of the world and our experience?

If there is a God, humans do have rights. Justice is something we are supposed to work for because black lives, blue lives, young, old, democrat, republican, gay straight, Muslim, Buddhist, all have tremendous value. They matter.

So when we condemn slavery and genocide, when we stand up for people's rights, when we protect the vulnerable, we are saying that humans have inherent value and rights (which only make sense if we're made in the image of God).

We live like God exists.

Meaning

Life has no meaning if God does not exist. We will die and so will humanity. Our achievements and our wars, our art, technology, and progress will be forgotten without witness as our sun burns down alongside the wider universe.

But try living a day like life has no meaning.

Why do you get out of bed? Why pour yourselves into work? Or kids? Or a cause?

We can delude ourselves with ideas like "subjective meaning" but subjective meaning is no meaning at all.

Albert Camus, the 20th century authority on meaning without God, summed up his life's work well - “There is only one really serious philosophical question, and that is suicide.”

Without God, nothing matters.

Is this an accurate description of the world and our experience?

With God, everything matters.

Our work, our parenting, our struggle for a better world are all of utmost importance. We are partnering with God on things that will last into eternity for people who will last into eternity. Even our incomplete, imperfect work awaits the day where God will complete what he's started in us.

In 1974, Ernest Becker won a Pulitzer prize for his book "The Denial of Death". Its core thesis: it is impossible for humans - religious or otherwise - to live as if life has no lasting meaning. We simply can't do it.

Does your life matter? My bet is that you live like it does - we can't help it. When we wake up, go to work, raise our kids, fight to make our world a better place we are saying that life has meaning.

We live like God exists.

Conclusion

Few non-theists work out the implications of their worldview. Fewer still have grappled with the incompatibility of those implications with real life.

If our boots have leaks, we need different boots. If our worldview can't account for reality, we need a different worldview.

A worldview without God has no room for fundamental aspects of our lives - and our humanity. Furthermore, it doesn't provide helpful guidance for living a good life. If anything, the opposite is true.

Back in the thick of my doubt, there were days where I was sure that God didn't exist. But I noticed something. Even on the days that I dismissed religion as a silly, inherited set of beliefs, I saw that it didn't really matter what theoretical conclusions I had reached about the existence or non-existence of God. I couldn't escape living as though God was real. It's just part of being human.

We live like God exists.

Comment

Do you live like God exists?

Subscribe

Share

Who could benefit from this post?

Hiking Boots and Worldviews

I was panicking on a cold Alaskan mountain.

My hiking boots had just soaked through. The temperature started to drop.

The realization sank in.

"What have I done?"

Boots

I was Caribou hunting in remote mountains east of Fairbanks. I was ill-equipped.

In planning for the trip, I had considered a few different hiking boots for the rugged Alaska terrain. It was unclear to me which boots were the best, so I chose some old cheap ones.

Big mistake.

On the first day, as we ascended the mountain, it rained. And then it rained some more. I felt my socks dampening. Then they saturated. As we climbed, the temperature cooled to near-freezing.

I would survive (and even get a Caribou), but the mist and showers would continue for the rest of the trip. My boots would never recover. I had to borrow from friends - socks, fire supplies (I ended up melting the boots trying to dry them out :/).

My boots looked good in theory from the comfort of my house. But they weren't ready to handle all that the real world threw at them. It was foolish and dangerous.

Worldview

Choosing a worldview is like choosing a hiking boot for an adventure. You think, you debate, and then you pick. Finally, you step out into the world to see how it works.

Choose well and you'll be ready for anything. Choose poorly and you'll find frustration and misery. You'll need to borrow from someone else.

What’s in a (Good) Worldview?

Oxford defines worldview as "a particular philosophy of life or conception of the world". Some get theirs from religion, philosophy, or their own brain. Many distract themselves so they never have to think about it.

What makes a good worldview? I think back to my own story and what I was looking for.

My searching boiled down to two questions:

What's true?

How do I live? (in light of what's true)

Some worldviews are better than others. Just like boots, some look cool and some are a little funky. For boots and worldviews, we need one that works. We need one that explains the world well and guides our lives.

If it can't do those things, we are in for discomfort and maybe even danger.

Many assume that if we simply walk away from God, then we don't have to worry about belief (or worldview) anymore.

But that's not how worldviews work. You don't abandon. You exchange. We've all got our mountain to climb, and barefoot is a choice (a very leaky one).

You can distract and ignore, but the worldview game is one that we all must play.

In my intro to this series, I mentioned a new worldview on the rise in America: the "nones" - call it atheism or agnosticism, the deconstructed or the deconverted.

In our next post, let’s put this view under the microscope.

Comment

How did you arrive at your own worldview?

Subscribe

Share

The Dumbing Down of America: An Intro to Neil Postman in 4 Quotes

“Push back against the age as hard as it pushes against you.”

-Flannery O’ Connor

Neil Postman doesn’t unveil a truth that you can’t unsee. Neil Postman gives you a set of glasses that you can’t take off.

For much of my life, I’ve felt like a fish out of water. It’s a feeling that started in high school and reached full germination in college and the years afterward. I’d had what most people would call “a religious experience” my sophomore year which set me on a deep, all-encompassing search for truth that would define the next decade of my life.

But while I set off to join the Great Conversation and hopefully figure out the meaning of life along the way, it seemed that nearly everyone around me was on a different path. Not that I didn’t enjoy a good movie or sporting event, but while I filled my time reading philosophy books and trying to understand the Bible and the Q’uran- I found that my friends were filling their free time watching NFL games and the Bachelor.

It wasn’t that we had different strategies- it was that we were playing a different game. I was simply optimizing my life for maximum understanding while they were optimizing for maximum entertainment.

Then I found Neil. His 1985 classic Amusing Ourselves to Death not only put words to what I was feeling- he gave me the cultural backstory, an expert’s diagnosis and more than anything Postman let me know that I wasn’t alone in the sea of American distractionism.

Let me introduce you to Neil Postman in four ideas through four quotes.

1. The Medium is the Metaphor

[My book] postulates that how we are obliged to conduct our conversations will have the strongest possible influence on what ideas we can conveniently express. And what ideas are convenient to express inevitably become the important content of a culture.

Imagine if Dave Chapelle went into a comedy club, got up onstage and instead of telling edgy, brilliant jokes- he read off a 10 page treatise on particle physics. Or flip it- imagine Stephen Hawking defending his PhD dissertation with one-liners on his professor’s poor haircut.

It doesn’t matter how funny Stephen’s jokes are or how penetrating Dave’s treatise is- they will both be booed off their respective stage.

In communication, the context (or the medium) defines everything.

Postman recognized this and more importantly he recognized that with the mass adoption of the television set, we had gone from the university lecture hall to the comedy club as an entire culture.

TV wasn’t an addition to our lives- it ushered in a completely new intellectual ecosystem- one that eventually produced a much different set of Americans.

2. The Peak of American Intellectual life (was 200 years ago)

“Americans no longer talk to each other, they entertain each other. They do not exchange ideas, they exchange images. They do not argue with propositions; they argue with good looks, celebrities and commercials.”

Abraham Lincoln met Frederick Douglas for a series of debates in the 1850s. The stakes were high and the debate would have been heated with the looming buildup to the civil war. For Postman, though, the stars of the show were not Lincoln and Douglas- it was the audience.

For instance, in 1854, after a 3-hour opening by Douglas:

“Lincoln reminded the audience that it was 5pm, that he would probably require as much time as Douglas and that Douglas was still scheduled for a rebuttal. He proposed, therefore, that the audience go home, have dinner, and return refreshed for four more hours of talk. The audience amiably agreed and matters proceeded as Lincoln had outlined.” (Amusing Ourselves to Death, p. 44)

What kind of audience was this? What kind of America was this where two educated men (not yet presidential or even senatorial candidates) could show up in a small Illinois town and farmers, butchers, and bankers would fill the seats so they could listen to complex oratory for seven hours (with zero pictures, of course).

While our Instagram generation glories in its chronological snobbery, a quick study of history or read of Postman, makes it clear that 19th and 20th century America was infused across class boundaries with a vibrant, literate intellectualism that hadn’t been seen before- and unfortunately- hasn’t been seen since.

3. The News Makes us Dumber

“Television is altering the meaning of 'being informed' by creating a species of information that might properly be called disinformation. Disinformation does not mean false information. It means misleading information - misplaced, irrelevant, fragmented or superficial information - information that creates the illusion of knowing something, but which in fact leads one away from knowing.”

We’re finally coming to grips with the idea that just because information exists does not mean we should take it in. While the science has just started coming in, Tim Ferriss has espoused his “low-information diet” for at least the last decade and Cal Newport has assembled a Digital Minimalist philosophy for our technological moment. While the sheer force of the digital information firehose has never been stronger, the seeds for information overload were planted centuries ago.

On May 24, 1844, Samuel Morse dispatched the first telegraphic message over an experimental line from Washington, D.C., to Baltimore. This ushered in a new age in American communication and facilitated a new connected age in American life.

For the first time a man in Iowa could get real time news of what was happening in Connecticut. The issue was that no one stopped to ask if Iowans needed to know what was going on in Connecticut.

Up until this point, the news and information available was regional and generally practical. The transition from the book to the telegraph introduced massive amounts of irrelevant, unactionable information. The resulting incoherence was not just a new practical problem but one that would alter Americans’ ideas about truth itself.

4. Technology as a Danger to Democracy

“If politics is like show business, then the idea is not to pursue excellence, clarity or honesty but to appear as if you are, which is another matter altogether.”

Where were you when Donald Trump won the US presidential election in 2016? The question on my mind as I sat in my apartment was: “what kind of country would elect Donald Trump?”

This wasn’t left-wing antagonism- it was a genuine question.

What were we looking for in a president? What value do we place on truth in our society? How has the internet age changed us?

That Donald Trump could have become president a hundred years ago- or even ten years ago- is laughable. But in the postmodern milieu of twitter, niche news, and all the rest- it makes perfect sense.

While republicans rejoiced and liberals sulked, my thoughts that election night were entirely on a question raised all the way back in 1985- have we amused ourselves to death?

Conclusion

After college, I tried to get my roommate to read “Amusing Ourselves to Death”. He couldn’t get through it. Too many arguments, not enough... pictures? I don’t know.

So, while the irony of a “quick blogpost” about the importance of medium and the supremacy of the book is not lost on me, perhaps it’s the appetizer our generation needs to the Neil Postman entree that just might keep us alive. Do yourself (and your country) a favor and pick up a copy.

As Neil’s son, Andrew, wrote in the 20th Anniversary edition:

“There’s still time.”

Comment

What role do you think technology / changing mediums has played in America?

Drop a thought below!

Subscribe

Share

Who might benefit from this post?

Images: Chappelle: John Bauld from Toronto, Canada, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons | Tim Ferriss: Julia de Boer / The Next Web, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons